Our Changing World for Thursday 28 July 2011

Self-setting Possum Traps

Goodnature’s Robbie Greig with a Henry possum trap (right), and one week’s tally from a single trap (photos: A. Ballance)

There are an estimated 30 million possums in New Zealand, and a new generation of humane possum trap might be just the answer for more effective trapping programmes over large areas. The Henry possum trap has been developed by Wellington design company Goodnature, working in close collaboration with the Department of Conservation. The trap is a self-setting trap, which can kill 12 possums before it needs to be reset.

The Henry possum trap is Goodnature’s third trap – their first design targeted rats, and then the design was modified for stoats and now possums. After several years of small-scale intensive testing to ensure the trap is completely humane and effective, the trap is now being used in several large scale trials being undertaken by WWF and DOC.

Alison Ballance joined designer Robbie Grieg for a walk into the foothills of the Orongorongo Valley behind Waunuiomata to check out a line of 10 traps that had been out for 8 nights. Although this area has been heavily trapped by the Goodnature team during several years of trialling, which meant possum numbers should have been low, the traps had nonetheless killed 37 possums – an impressive tally, especially as the traps had not required any time-consuming checking since they were put in place.

Unearthing an Ancient Culture

Hallie Buckley and Rebecca Kinaston excavating a skeleton at a late-Lapita cemetery site on Watom Island, East New Britain, Papua New Guinea, in 2008.

In 2003, a digger driver who was excavating soil for a prawn farm on Vanuatu’s main island Efate discovered a richly decorated shard of pottery. He recognised it as something unusual and took it to the local museum, where a curator identified it as a piece typical for the pottery created by Lapita people. The serendipitous discovery sparked the interest of archaeologists from New Zealand and Australia, led by Stuart Bedford, who soon unearthed not just more pottery but human remains, confirming that the site was a Lapita cemetery and, at about 2800 years, possibly the oldest burial site in the Pacific region. The Lapita are ancestors of modern Polynesians and have dominated the exploration of and expansion into the Pacific. This site is thought to include some of the earliest people to make landfall in Vanuatu. After several seasons of excavation, the team unearthed a total of 67 burials, including nearly a hundred individuals, most of them headless. University of Otago bio-archaeologist Hallie Buckley has examined the bones to shed light on how these ancient explorers lived, what they grew and hunted, and the diseases they suffered.

Icebergs – a Science and Art Conversation

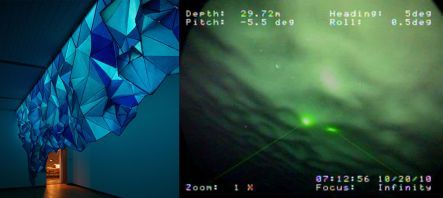

Gabby O'Connor's iceberg in the 'What lies beneath' exhibit at Wellington's City Gallry (photo: Andrew Beck), and photograph of the underside of the Erebus Glacier tongue, taken by an underwater ROV (photo: C. Stevens)

Sculptor Gabby O’Connor has a fascination with Antarctica, both the place and its history, and she has turned that fascination into a room-sized iceberg installation. The iceberg, which is installed in the Hirschfield Room at Wellington’s City Gallery until 31 July in an exhibition titled ‘What lies beneath’, is made from 3000 sheets of tissue paper and 28,000 staples, and is suspended beneath the room’s ceiling light well.

Craig Stevens is a marine physicist at NIWA, with a special interest in turbulence and water movement. He was in Antarctica in November 2010, as principal investigator on a project called ‘Cold Spice – double diffusion generated by vertical ice walls’, also know as the Glacier Tongues and Ocean Mixing Research Project. The project is looking at turbulence and mixing in the water and ice boundary layers under the Erebus Glacier ice tongue, with a view to better understanding global ocean processes in a warming world.

Gabby and Craig presented a lunchtime talk at the City Gallery in which they talked about their projects, their experimental approaches, and the overlaps they see in the processes of science and art. Alison Ballance recorded the conversation for Our Changing World.

Glass Harmonium and Singing Rods

Alastair Galbraith playing the glass harmonium (image: Alister Reid)

With laboratory glass, and the talents of glass-blower Anne Ryan from the University of Otago, Alastair Galbraith has created a musical instrument called a glass harmonium. The first mechanical glass harmonica was invented by Benjamin Franklin and composers like Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart wrote pieces specifically for the instrument. To see some of the glass being blown for the glass harmonium, click here.

Glass “bowls” are arranged with smallest on the left, to largest on the right, with a sewing machine treadle to spin the rod, like a rotisserie. The sound produced is similar to the sound of running a finger around different-sized wine glasses. Ruth Beran visits Alastair Galbraith at his home in Taieri Mouth, where he plays the instrument for her. To do so he dips his fingers in a mixture of lemon juice and water to stop grease accumulating on the glass. To listen to a previous Our Changing World story on scientific glass blowing, click here.

While there, he also shows her some aluminium rods, which sing when squeezed the right way. The rods have to be held with one hand, either in the exact middle or at specific points along the rod, and then squeezed with the fingers of the other hand after being dipped in sticky violin rosin (pictured left. Image: Alister Reid). The motion causes a longitudinal wave, vibrations which travel the length of the rod. For more information on how these waves create sound, click here.

To listen to last week's Our Changing World story on Alastair Galbraith's flame organ, click here.