Tonga is bracing for the full force of Cyclone Gita this evening, with memories still fresh of another category five storm which caused major damage four years ago.

Cyclone Ian hit the outer Ha'apai island group in 2014, leaving thousands homeless.

Massive damage remains after Cyclone Ian.

Photo: Richard Small

By 7 pm Tonga time, Gita is forecast to become a Category Five cyclone, the highest level in the region's cyclone grading system.

It's making a beeline for the main island of Tongatapu, home to the capital Nuku'alofa and most of the population.

Gita will be the fourth category 5 cyclone to hit the Pacific since 2015. With each one, homes, infrastructure and livelihoods of the Pacific Islands in its path stand to be devastated.

Scientists have linked climate change to increased severity of cyclones, although not necessarily the frequency of cyclones.

Direct hit looming

A direct hit by Gita on Tonga will mean another major recovery effort for the small island state.

Following Cyclone Ian, the reconstruction effort on Ha'apai was plagued with delays and an investigation was ordered into missing funds meant to go towards the rebuild.

Gita is the first high magnitude cyclone to hit the Pacific island region this season which runs from November to April.

NIWA predicted eight to ten in the southwest Pacific, and up to six of them to be Category 3 or higher.

Cyclone Winston was the last Category 5 cyclone to hit the region, scoring a direct hit on Fiji in February 2016, killing 44 people, displacing tens of thousands and causing US$1.4 billion worth of damage.

Today the rebuild is still underway and many children are still learning in tents as the country tries to build back stronger.

At least 15 people died a year earlier in Vanuatu when the "monster" Cyclone Pam hit, causing widespread damage.

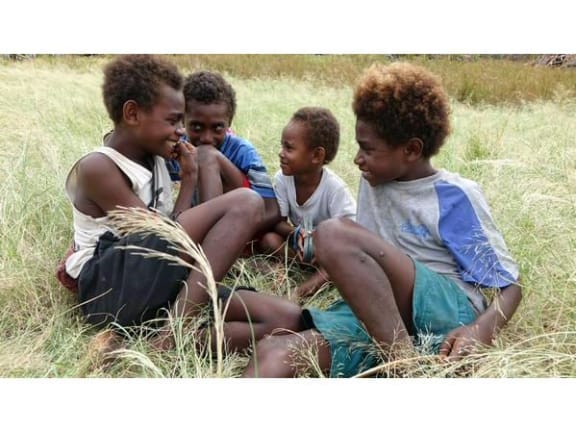

A medical team from the Superyacht Dragonfly run an emergency medical clinic at Cooks Bay Erromango. Children were getting cuts from all the debris left by the cyclone and without proper care many were getting badly infected.

RNZI reporter Koroi Hawkins arrives at Whenuapai for possible passage on a defense force flight to Port Vila. 16 March 2015.

Squadron Leader Steve Thornley is heading up the Vanuatu missions. He says when flying over Tanna Island they saw a lot of destruction. 16 March 2015.

Relief supplies bound for Port Vila being loaded at Whenuapai air force base. 16 March 2015.

First RNZAF C130 Hercules leaves for Vanuatu at 10:30am. Flight time 5 hours. 16 March 2015.

Hanna Butler of the New Zealand Red Cross says the humanitarian needs in Vanuatu are expected to be overwhelming. 16 March 2015.

Second Hercules departing Whenuapai. RNZI reporter Koroi Hawkins will soon be reporting from Port Vila, Vanuatu. 16 March 2015.

Vila Bauerfield International Airport reopened. 16 March 2015.

Vanuatu red cross volunteers unpack relief supplies for distribution as soon as they are off the planes. 16 March 2016.

Evidence of cyclone Pam. Vila Airport yet to receive first commercial flight. 16 March 2016.

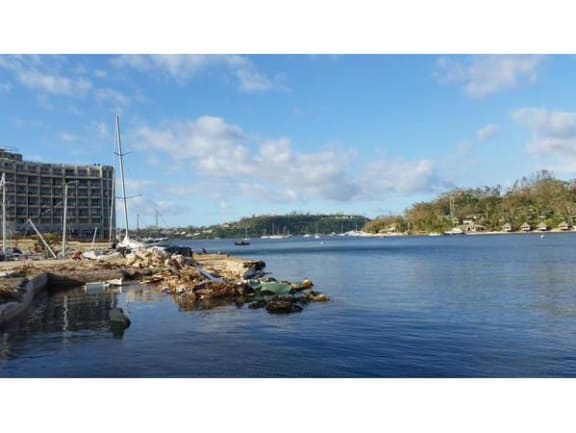

Port Vila. Power is out. Water runs only in some places. Police Curfew has started. There is so much destruction. Koroi Hawkins. 16 March 2015.

Birds chirping in leafless trees in Port Vila. 17 March 2015.

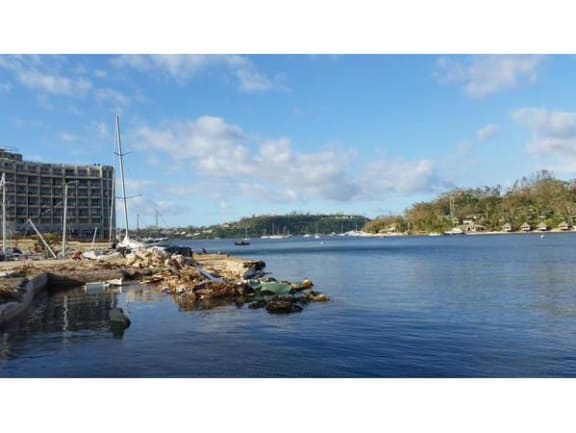

Many boats are lying along the shore in Port Vila. They are the lucky ones. Others are at the bottom of the ocean. 17 March 2015.

Command center, Vila National Disaster Management Office (NDMO). 17 March 2015.

Vila National Disaster Management Office control center bustling with activity. 17 March 2015.

In Vila you can hear hammers banging as people try to rebuild lives. A bus driver asked if there was another cyclone coming. 17 March 2015.

The National Disaster Management Office has confirmed the death toll as 11, five on Tanna Island, six in Vila. 17 March 2015.

Heading out to Fresh Wota settlement, Vila's most populous. An evacuation centre has been set up at the school. Reporter Koroi Hawkins is both curious and apprehensive about what awaits him.

Fresh Wota School evacuation centre. Population 600 - equals 600 moving stories. 17 March 2015

Fresh Wota residents Ralph & Mary Yalu and family. Their home was destroyed by cyclone Pam. Their local school is also gone. 17 March 2015.

Relief supplies arrive at Fresh Wota from National Disaster Management Office. Drinking water and food are the major needs here. 17 March 2015.

A ray of hope. Mary Yalu lost her home but gained a grandchild. Pamina is one of many babies born during cyclone Pam. 17 March 2015.

Electricity and water suppliers UNELCO are hard at work. This crew say electricity is restored to many areas, but say it will take months to restore the full grid. 17 March 2015.

National Disaster Management Office truck returns to HQ after relief delivery to evacuation centres. The items include rice, canned food and toiletries. 17 March 2015.

Vanuatu volunteers store donated goods. Most are victims yet work all day with a smile. It is remarkable and humbling. 17 March 2015.

As far as the eye can see in every direction everything is torn, broken or simply no more. paradise lost...for now. 17 March 2015.

The perks of a blackout in Vila. No lights but all the stars are out. 17 March 2015.

Good morning from Vila. Heading to the hospital hoping to speak with the medical superintendent about the situation there. 18 March 2015.

The medical superintendent at Port Vila hospital says a large influx of patients is straining resources but that a mobile hospital to be staffed by Australian and NZ doctors arrives today.

Red Cross Vanuatu says it will wait for National Disaster Management Office to give the OK before it starts distributing supplies. 18 March 2015.

Save The Children says it is already distributing food and basic items to 2000 homeless in Vila, with the government's knowledge. 18 March 2015.

On my way to Mele village. I've heard root crops are inundated, a huge problem for many who rely on gardens for survival. - RNZI Reporter Koroi Hawkins.

A story reporters hear often: "Now we have a water view... we didn't before." 18 March 2015.

Books drying on a slab that used to be the Melemaat Primary School, with 400 students. Schools in Vanuatu will reopen in a few weeks.

A creek at Prima still runs muddy. Houses and remnants of houses lie scattered across the muddy wasteland.

About to take off for a flyover of Efate. Plane door removed for better video shooting.

The Maule is a STOL (short takeoff and landing) aircraft based in Torba Province, run by Wings of Hope flying doctor service in Vanuatu. Reporter Kim Baker-Wilson has butterflies.

Vila looks beautiful, yet desolate from the air.

Emergency banking is available at Tyock Street, Vanuatu - at the ANZ manager's residence. The main branch is yet to reopen. 18 March 2015.

Measles vaccinations are ramping up in Vanuatu after the cyclone. 18 March 2015.

The race to immunise against measles in Vanuatu. 19 March 2015.

Waiting at today's vaccination drive. 19 March 2014.

The children's ward at Port Vila's hospital was a hard place to be. KBW 19 March 2015.

Vanuatu's Director General of Climate Change Jotham Napat says aid distribution starts tomorrow (20th March). Vanuatu State of Emergency declared 18 March.

Chico farm in Teoma has been selling live chickens for 200 vatu - 300 less than before the cyclone. It was too popular. 19 March 2015.

Women and children bathe in water gushing from the rocky hillside at Number 2 lagoon. Heavy rains made this torrent. 19 March 2015.

Relief deliveries have started for Vila. Buses filled with food and other items are on their way. Still no shelter kits but it's a start! 19 March 2015.

NDMO staff say a ferry laden with relief supplies left for Tanna Island tonight. They say more ferries will be loaded tomorrow. 19 March 2015.

Still no power for us in Port Vila. Reporter Koroi Hawkins makes the most of the battery left in the laptop. 19 March 2015.

The newspaper is back in print as electricity to parts of Vila continues to be restored. The front page questions relief aid delays. 20 March 2015.

Govt tax exemptions on building materials are coming into effect. There is a private sector forum on economic recovery today. 20 March 2015.

A mobile hospital is being erected at Vila hospital to help with influx of patients from cyclone Pam.

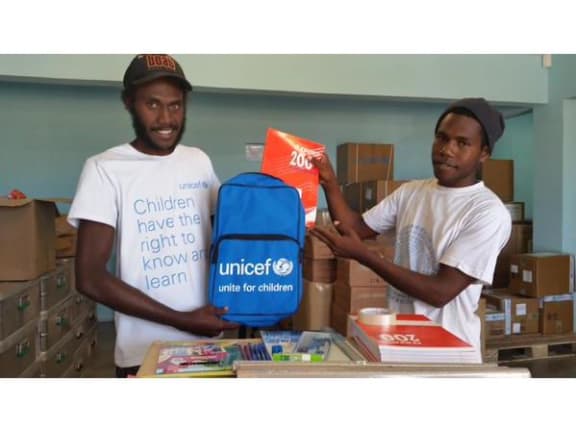

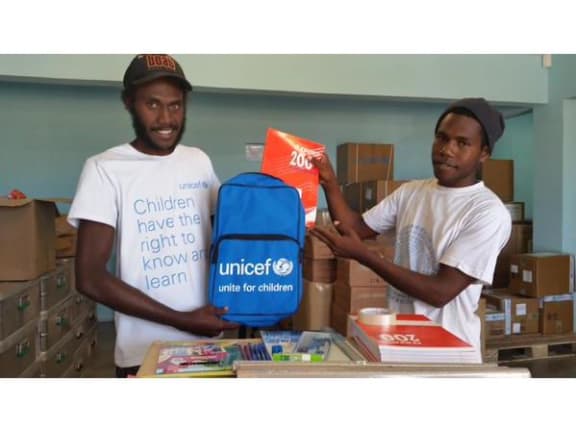

Unicef volunteers packing 700 school kits for Vanuatu kids affected by Pam. Many schools have been destroyed.

I am going out on the barge Epi Dream to the Shepherd Islands during the the next 3 days. The group was hit badly by Pam. - reporter Koroi Hawkins.

Helping to fill 2000 x 10 litre water containers to go to Shepherd Is. Only one hose pipe. Could be here a while!

Thank goodness for splitters!

D.I.Y efficiency in action.

Progressing well, still a little over thousand to go I think. Six hoses now, and the one from the nearby depot is high pressure. 20 March 2015

Barge has arrived. Now we load it!

Loading 50 x 25kg rice bags to go to Shepherd Islands

Chain gang loading water onto the Epi Dream barge bound for Shepherd Islands.

And we're off. Have tonnes of water, food and medical supplies, and personnel. Hope it's enough. The sea is rougher than expected. First stop Matapoa ETA 2:00 am VUT.

Dawn on Saturday 21 March. Arriving at Mataso Island.

There is no landing so we run up the Mataso island beach. I'm with a doctor, a nurse and a guide. Don't know what to expect.

No shelter kits have reached Mataso in the 7 days since Cyclone Pam.

Rachel, Naomi and little Joycelyn rest in a bit of shade.

A makeshift prayer bell swings over the wreckage of Mataso Island's church. Everyone I meet here says God Bless You.

A woman died of head injuries 6 days after Cyclone Pam. There were no medics here. Grandchildren placed their gifts to her on the grave. 23 March 2015.

Saturday. No medicines in Mataso. Dr Jim said dehydration, respiratory illness and infected cuts are the main concerns. 23 March 2015.

The force of nature. A wide shot of a destroyed house on Mataso island.

Something shiny buried in a tree trunk. Probably roofing iron.

These lads on Mataso made the most of the destruction around them, turning this coconut into a seesaw trampoline. 23 March 2015.

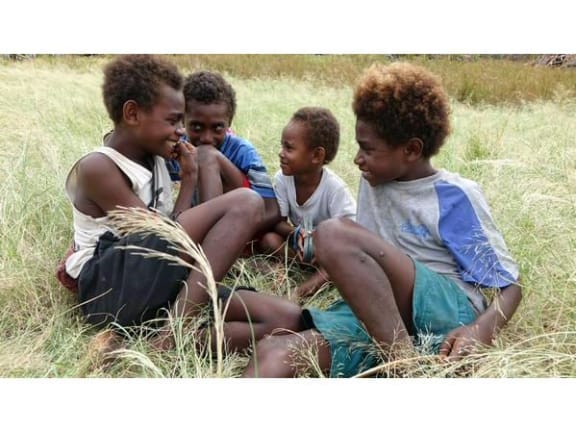

Mataso kids have lost their school.

Some Mataso kids were sick and getting cuts from debris. Dr Jimmy warned them to be careful.

This baby on Mataso was not shy and kept trying to grab the camera. There was no medicines or shelter at the time.

Mataso people have had no water, shelter or medicine for 6 days. The supplies we left are only enough for a few days.

Heading to Epi in the Shepherds group now. 23 March 2015.

South Epi was hit hard by Cyclone Pam.

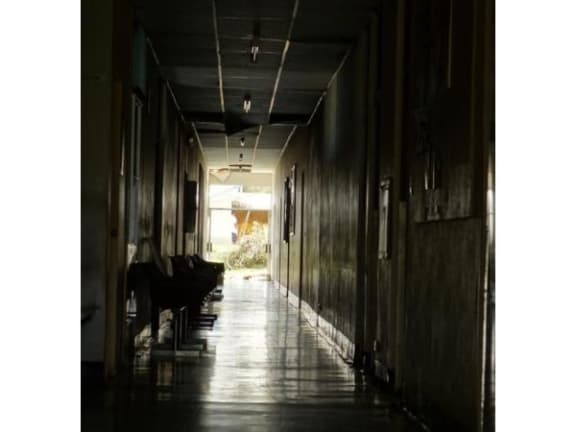

No learning here at the moment.

Finally I can talk about good news! Helicopter drops water container on South Epi. 24 March 2015

So some help is getting through, and PM says a boat is leaving Vila this morning for these areas.

Helicopter drop includes water and rebuilding supplies. 24 March 2015.

Sakaio and Tessa Cook and family. 23 March 2015

Sakaio and Tessa Cook show me where they hid from Cyclone Pam after telling their children to save their grandchildren.

Sakaio and Tessa Cook and family at home. 23 March 2015

The clinic at Emae was damaged by Cyclone Pam. 24 March 2015.

1200 Emae people are affected and now have poor access to medicine.

At Lemanu Island, North of Epi. Its better off than other areas but they said this was the first relief to reach them.

Nurse Leiwia stands where she delivered Lemanu's cyclone baby Patrick Pam. She says medical supplies are low. 23 March 2015.

Hope to be back on Mataso tody for first time since Saturday. Praying everyone is okay and hoping relief has got through. 24 March 2015.

Last day in the Shepherds has been very heartwarming was able to return to Mataso and see some meaningful assistance. 24 March 2015.

I've helped clear tree-blocked paths and translated for a medical and water purification team. So happy to help a little. 24 March 2015.

Mixed emotions at the medical tent. 24 March 2015.

Met baby Joel again he got a clean bill of health. Good to see relief getting to Mataso. Hope recovery starts soon. KH 24 March 2015.

Steaming towards Eramango 25 March 2015.

Eramango was directly hit by Pam. 25 March 2015.

It's two weeks tomorrow since Cyclone Pam. 25 March 2015.

Got there this morning no food or shelter relief has reached them. 25 March 2015.

Child on Eramango 25 March 2015

Eramango chief Jason Mete interviewed on satellite phone. The first phone call since Cyclone Pam. 26 March 2015.

People came out to watch. 26 March 2015.

Tanna Island. Everywhere so far food is down to a few days supply. So many villages so few resources very little time. 26 March 2015

Water airlifted to villages on Tanna. 26 March 2015

Warship off of Tanna. Has Blackhawk helicopters on it. 26 March 2015

"Flying out of Vanuatu I leave my heart behind with the beautiful people in all the villages I have been to" Koroi Hawkins. 29 March 2015.

Traditional means of coping

The people of the Pacific are well used to the ravages of cyclones, and have traditional means of coping when monster storms approach.

They know the best parts of their island in which to shelter, which trees are the strongest, and which caves can be used in the case of an emergency.

Even the traditional Pacific fale-type home structure can offer more flexibility and resilience in a big storm than more modern, ramshackle homes built with corrugated iron and planks of wood and the ubiquitous and sturdy churches make safe boltholes in the eye of a storm.

Resilient concrete homes are more commonplace these days in Nuku'alofa but still, as borne out during Cyclone Winston in Fiji, they are not failsafe.

Small island states, increasingly at risk from more frequent and intense storms zigzagging their way across the Pacific, have shown resilience in picking up the pieces after big storms hit.

But there is no avoiding extensive damage not only to homes but roads, schools and other infrastructure when a cyclone passes over an island.

Devastating cyclones are just another pressure for the small, aid reliant countries of the Pacific.