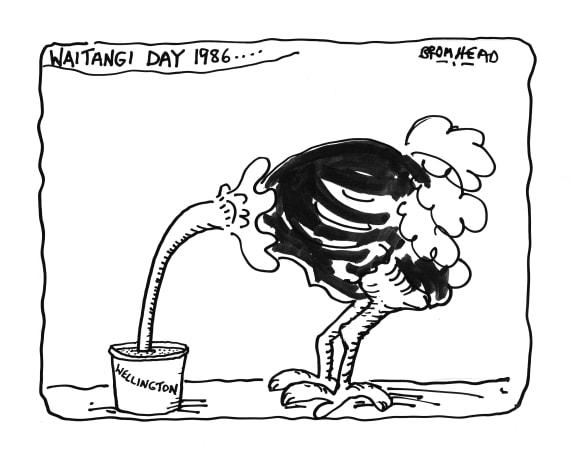

Newspaper cartoonists job is to cast a critical eye on what’s going on and sum it up in images that can be understood at a glance at that time. But author Paul Diamond tells Colin Peacock cartoons about Waitangi Day and the Treaty down the years also serve as a snapshot of the past - and recent history too.

Paul Diamond with Lousia Wall MP and Ella Diamond. Photo: National Library

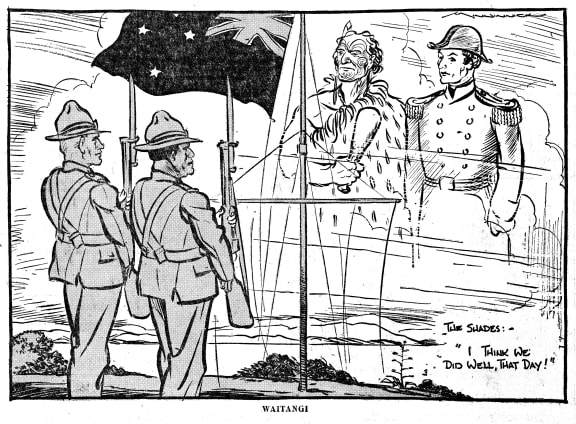

100 years after the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, the New Zealand Herald carried a cartoon by long-serving artist Gordon Minhinnick.

Looking down on a Māori and a Pākehā soldier standing side by side at Waitangi, the ghosts of Governor Hobson and a rangatira agree: “I think we did well that day.”

It wasan image of harmony to mark the centenary in the nation’s paper of record the day after the anniversary. It was also a time of war in which Maori and Pākehā alike were encouraged to serve King and Country.

But some Māori leaders boycotted the celebrations and on the day in 1940 and no less a figure than Sir Apirana Ngata said Māori had much to regret.

“What did the Māori see? Lands gone, the power of chiefs humbled in the dust, Māori culture scattered and broken,” he said at Waitangi.

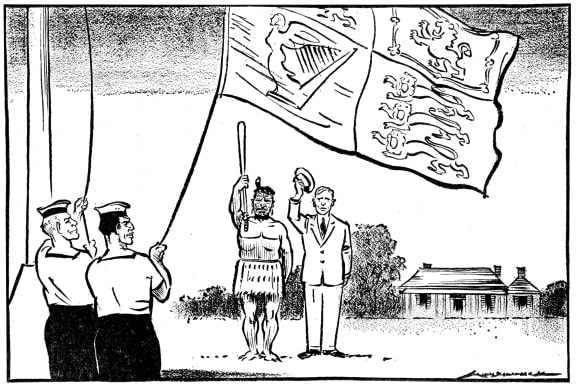

23 years later on Waitangi Day, Minhinnick reprised the bi-cultural image in the Herald.

There were no words this time - not even a title - just a Maori and a Pākehā soldier were raising a flag while a Māori man with piupiu salutes them with a raised taiaha and a Pākehā bloke in a suit doffing his hat.

The flag is the Royal Standard and the Queen had just landed for a royal tour.

Another image suggesting all was still well among the races on Waitangi Day 1963?

Savaged to Suit: Māori and Cartooning in New Zealand, by Paul Diamond. Photo: Supplied

In his recent book Savaged to Suit, Turnbull Library curator Māori Paul Diamond (Ngati Haua, Te Rarawa, and Ngapuhi) took on the job of interpreting Māori in cartoons.

“I think its a message about the way the readers of the new Zealand Herald - and the editors - saw race relations at that time,” said the author and historian.

An entire chapter of his book is devoted to how the Treaty and Waitangi Day itself has been depicted down the years.

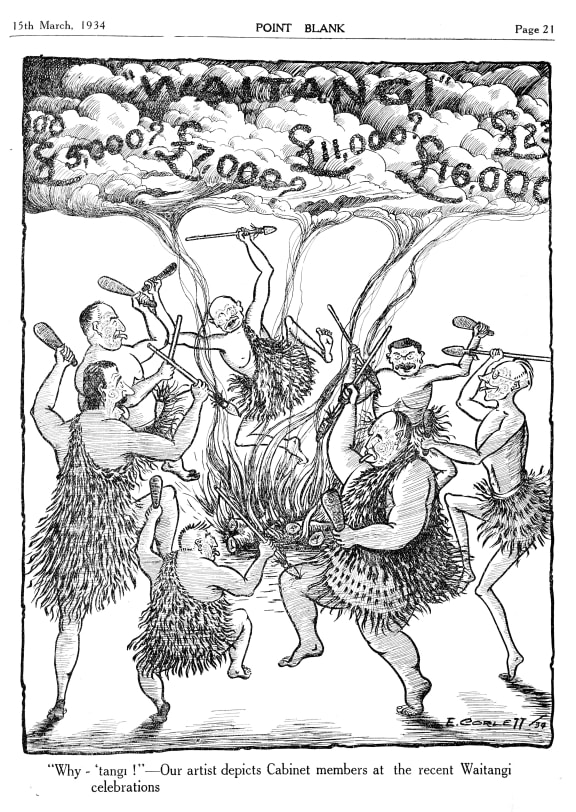

The cartoons first crop up after the first official commemoration in 1934.

A month after the celebration that year the New Zealand Farmers’ union paper Point Blank criticised it in cartoon depicting cabinet ministers of the day in Māori dress dancing around a fire in which money was going up in smoke.

It would be another forty years before newspaper cartoons seen by a mass audience acknowledged Māori anger over breaches of the Treaty and protests at Waitangi Day.

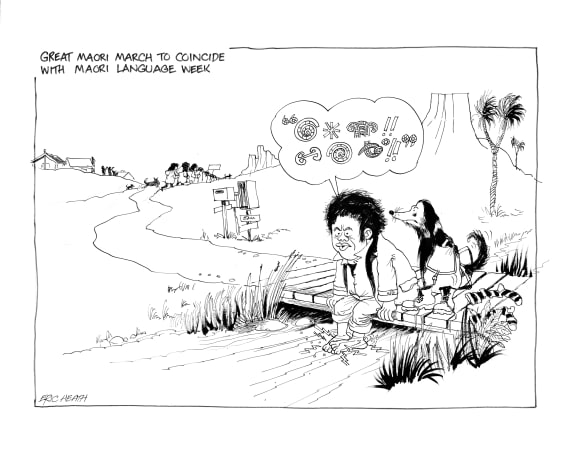

Paul Diamond notes in Savaged to Suit the notion of “protests as a puzzling novelty gave way to scepticism and anger” in some cartoons.

“Some cartoonists tended to reflect the editorial line of the papers they cartooned for. They reacted with bemusement and didn't engage with the content of those protests.”

Land marches culminating in hikoi to Parliament in October 1975 could not be ignored. Cartoonists confronted the issues which prompted Dame Whina and thousands more to trek to Wellington.

Gordon Minhinnick - who cartooned for the Herald until the late 1980s - drew one featuring land marchers arriving in Wellington finding old Parliament buildings demolished as the Beehive was being built alongside.

“By golly! It was there when we left,” one marcher tells others in the cartoon.

“This acknowledges there was a protest happening - but doesn’t engage at all with what the march was about,” he said.

“(Minhinnick) was one of the last to stop using using shorthand markers like a huia feather and phrases like ‘pi korry’ / ‘by golly,” he said.

“It reaches back into depicting Māori as a bit silly,” he said.

But other cartoonists of the time picked up on the anger and seriousness of the protests - and what sparked them.

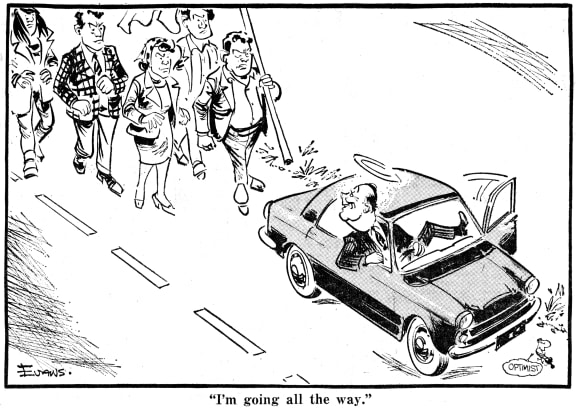

Malcolm Evans - still cartooning today - notes how Robert Muldoon (then opposition leader) co-opted the land march. He was the first politician to meet the marchers in Wellington and one Evans 1975 cartoon shows Mr Muldoon offering to take them the last mile in his car.

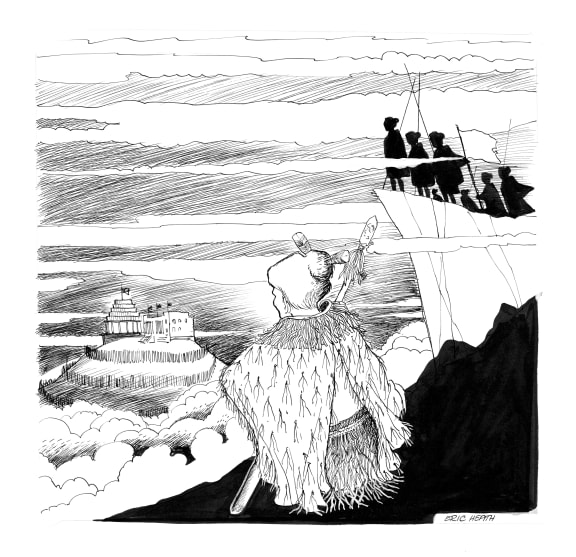

On the day the marchers arrived, Wellington’s Dominion published a telling Eric Heath illustration on its editorial page.

“He’s drawn Parliament as a pallisaded pa site, besieged - but shows also the dignity of the marchers. He’s wondering what we were on the verge of. He did grasp the significance of the march,” he said.

In the Dominion ten years later, Eric Heath’s ‘Waitangi comes to Wellington’ was a simple image of Beehive toppled Hone Heke-style by an axe.

The day before, the Treaty of Waitangi Amendment Act was passed to give the Waitangi Tribunal the power to investigate breaches of the Treaty back to 1840.

“That’s the genius of these people. They have to have a take on it within 24 hours of it happening,” he said.

In Savaged to Suit, Paul Diamond sees “bewilderment and humour” in Waitangi-themed cartoons giving way to expressions of “Pākehā insecurity” in the 1980s

Some cartoons highlighted the flaws in the Treaty exposed by the airing of subsequent claims.

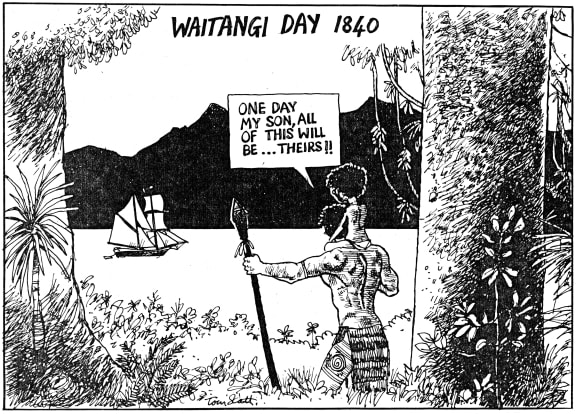

One of the most-remembered is Tom Scott’s ‘One day my son, all of this will be ... theirs' cartoon published on Waitangi Day 1988.

Paul Diamond this was an image which did not merely reflect the editorial line of the paper - or most readers.

“There are situations where (the catroonists) think: ‘Come on people - you need to be aware of this’. But there will be other situations where they are representing what they think people on the bus and the train are talking about,” said Paul Diamond.

But until this point, almost all the cartoons people saw in their papers were by Pākehā artists and from a Pākehā perspective.

There were exceptions.

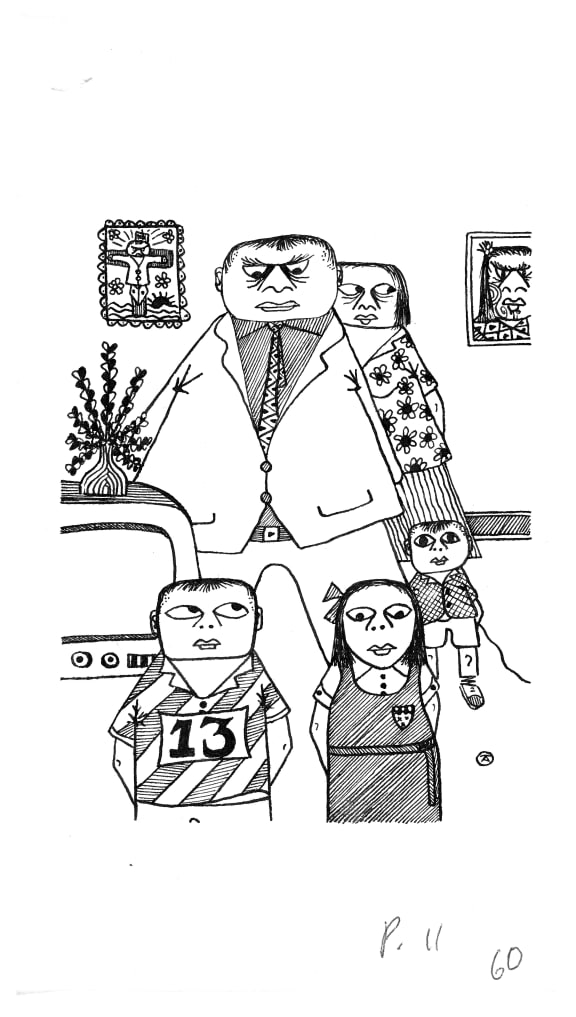

Harry Dansey - who later became a race relations conciliator - was a journalist as well as a cartoonist from the 1950s onwards.

“I am not on the outside looking in because I am proud of the blood of both races which has been handed down to me,” he wrote in a 1959 essay called Of Two Races.

More recently Māori cartoonists like James Waarea and Anthony Ellison tackled racial issues in the pages of mainstream papers.

Paul Diamond said Anthony Ellison - who later moved on to cutting-edge animation - clashed with editors because he refused to stereotype Māori characters and women in his images.

“That tells you something about the climate he was working in,” he said.

Image from Savaged to Suit, Paul Diamond's latest book Photo: supplied

Some of Ellison’s cartoons in Savaged to Suit cleverly address racial issues without depicting anyone at all.

In a 1989 cartoon about the Māori Fisheries Bill an open can labelled 'worms' reveals another can labelled 'more worms', and another labelled 'even more worms' inside that.

“It exploded from the 1990s with the prominence of the Treaty and also MMP. More Māori in parliament it put Māori issues and politicians into the orbit of cartoons.”

Current cartoonist Sharon Murdoch is one of only a handful of women of Māori heritage working in mainstream media.

So have things changed in the digital era?

“There is less stereotyping today,” Paul Diamond says.

“We have a whole different audience that won't necessarily ‘get’ the old huia feather and bare feet imagery that would have been familiar to our parents and grandparents.”