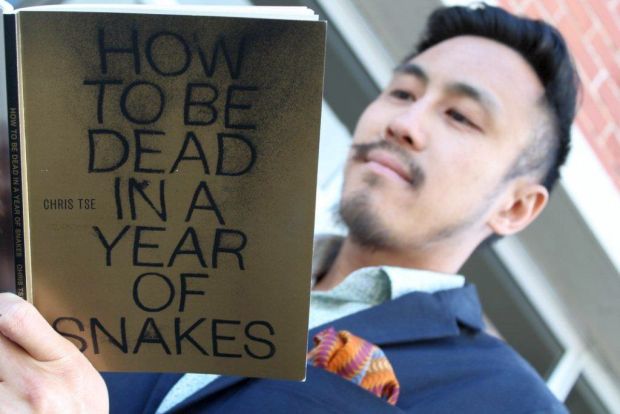

Chris Tse reads from his book, on Haining Street

He would have been the ghost who wanders, removed and homeless, because he wasn't buried in his home, back in China.

– Chris Tse from his book How to be Dead in a Year of Snakes (Auckland University Press, 2014)

Chris Tse tells me his name rhymes with peace, as we traverse Haining Street, Wellington. It's the site of the murder scene of elderly Chinese gold miner Joe Kum Yung.

Haining and Frederick Streets (off Taranaki Street and in the CBD) were the sites of the old 'Chinatown' of Wellington. Virtually nothing is left of this Chinatown, today its office buildings, urbanised apartments and lots of passing traffic.

How to be Dead in a Year of Snakes is Chris's first book of poetry, published with Auckland University Press in late 2014 and it's already garnered critical acclaim. He's reading excerpts at the spot where Joe Kum Yung lay dying, fatally shot by white supremacist Lionel Terry, 110 years ago in 1905.

The memorial plaque to murder victim Joe Kum Yung

According to historical accounts, Lionel Terry took his gun that day and shot a 'Chinaman', an innocent member of the public, to help eradicate the 'yellow peril'. Terry saw himself doing a service to the community.

Even though it's 110 years on it still gives me a chill to visualise the cold-blooded actions of Lionel Terry. Chris's book evokes the voices of the dead into our living present with haunting lyricism.

Why the title? Because 1905 was in the Chinese year of the snake and because Chris was fascinated by the underlying cultural and spiritual beliefs that colour each year of the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac. It's not that Chris wishes to demonise snakes, rather, he uses the year of the snake as the cultural and spiritual backdrop to replay some of our own unsavory history.

It's taken 10 years for Chris to write this book, from the earliest explorations of this subject matter during his Masters degree in Creative Writing at Victoria University's International Institute of Modern Letter in 2005. This was also the centenary of Joe Kum Yung's murder.

At the centenary in Haining Street there was a lot of activity acknowledging the event but it had always been more of Lionel Terry's story. Who owns the story? I wanted to show the flip-side, present a different view - the murder victim's view.

Public fascination has always lain with Lionel Terry in this politically and racially motivated hate crime.Chris wanted to turn this around. He wanted to give the murder victim, Joe Kum Yung a voice, back from the dead.

Chris's book is dedicated to his late Por Por (Cantonese for maternal grand-mother). It was her passing in 2011, when his family practiced ching ming, appeasing their ancestor with offerings of food and the burning of joss-sticks, that he formulated the idea of interviewing the ghost of Joe Kum Yung and other ghosts of Haining Street.

It's very important in Chinese culture to practice ching ming so that the ghosts of the dead won't wander, hungry and lonely.

Because the victim had largely been ignored by history, Joe Kum Yung had become a lost voice, a wandering ghost. Chris also interviews Lionel Terry but he was careful not to let Lionel's story overshadow Joe Kum Yung's.

Haining Street

After traversing Haining Street we conclude the interview back at the spot where Joe Kum Yung lay dying. It seems fitting to hear more of his voice, to give Joe Kum Yung the last word so Chris reads me more excerpts from his book:

I rest now with my tongue silenced, words

cast out beyond my reach.

The night

embraces all, still as a headstone ...