Vanuatu - a brief history

Vanuatu is believed to have been settled by Austronesian-speaking peoples around 1200-1300 BC. One of the earliest known leaders was the Chief Roy Mata, who united a number of tribes in 1200AD. The chain of 80 Melanesian islands running north from Fiji and New Caledonia to the Solomon Islands has suffered much from foreigners with conflicting interests. Early 17th century Spanish, French, Portuguese and British explorers were followed by 19th century raiders and privateers keen to plunder the resources of the group named The New Hebrides by Captain James Cook.

Early devastating exploitation and the curious 'condominium'

By 1825 every sandalwood tree had been felled and hundreds of islanders had been bullied, killed or dragged away to slavery in Australia by disreputable traders.

Missionaries began arriving in 1839 but early conversion attempts were often thwarted. They persevered and were allowed to evangelise. Unfortunately, they also introduced smallpox, influenza, pneumonia and other diseases which killed many of the converted.

British and French naval ships dominated the waters off Vanuatu with the sole purpose of keeping out rivals. In 1888, they signed a Joint Naval Agreement, the first of many ill-founded compromises imposed on the islanders who later became the ni-Vanuatu. In 1906 Britain and France set up the Condominium of the New Hebrides – a unique, absurd colonial construct. Its Court consisted of British and French Judges, a Dutch Registrar and a Spanish President who spoke little French and less English.

Over the 76 years of what soon was called the Pandemonium, British and French administrators ran separate police, education and other services.

The 100,000 or so islanders, separated already into 110 language groups, were further divided into anglophones and francophones. Chinese and Pacific French farmers came to buy land despite the New Hebrideans' objections.

In 1958 an Advisory Council was established, increasing local hopes that land sales would be stopped and decolonisation started, but those hopes quickly fell away. In 1959 President de Gaulle declared France would keep control of her Pacific territories. Soon after, Prime Minister Macmillan declared Britain was to leave her colonies. For a further twenty years, colonial conflict would bedevil constitutional progress.

Pressure for political change

In 1971 returning ni-Vanuatu graduates began to work for political change, while French officials encouraged land sales to settlers supporting colonial rule. The British (anxious that France support their bid to join the EEC) colluded with French authorities to delay political progress.

In the 1975 election of the first Representatives Assembly, the largely anglophone New Hebrides National Party (NHNP), led by Father Walter Lini, won most ni-Vanuatu votes but was denied majority control by six members appointed by the Resident Commissioners. The NHNP boycotted the Assembly. When requests for a more democratic system were refused, the party refused to take part in the 1977 election. A minority government was installed and public protests were quelled with teargas. French officials encouraged disruptive groups on the island of Tanna and Nagriamel, a northern secessionist movement which would continue to cause trouble after independence.

In the 1979 Representative Assembly election, the Vanuaaku Party (formerly the NHNP) won 62% of votes and 26 of the 39 seats. Believing the country's future should be determined at home, it boycotted constitutional meetings in Paris but attended discussions in Port Vila until a new constitution, restricting land ownership to ni-Vanuatu and entrenching French culture, was agreed by 'Melanesian consensus'.

Independence at last

However, Vanuatu's Independence Day – like its 74 years of Condominium history - was soured by its colonial masters. On 30 July 1980, cheering crowds filled the capital. But the flag-raising in Luganville on Espiritu Santo was jeered by Nagriamel supporters. Also there were British and French troops, sent at the insistence of the French until the new government guaranteed protection to French interests.

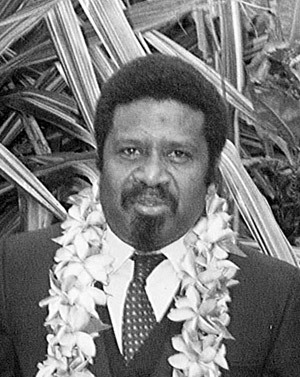

The man who had to resolve this colonial interference was Prime Minister Walter Lini. An Anglican priest who became known as the father of independence, he was born in Pentecost and brought up as an English-speaking New Hebridean.

Significant events since independence

August 1980 Lini Government sends French/British troops home; asks Papua New Guinea to help. Terrorist activity on Santo increases.

PNG troops arrest Jimmy Stevens and some foreigners.

September 1980 PNG troops leave. Vanuatu Police charge several hundred people associated with rebellion. Jimmy Stevens sentenced to 14.5 years prison.

1981 Most prisoners released. Vanuatu official denied entry to New Caledonia. French Ambassador asked to leave Vanuatu.

1983 Vanuaaku Party re-elected.

1987 Vanuaaku Party splits; Coalition governs under PM Lini.

1991 Coalition of Vanuaaku/Union of Moderate Parties governs under Maxime Carlot Korman (first francophone PM).

1996 Coup d'etat attempt fails.

1997 Asian Development Bank programme; tax/public service reforms

1999 Father Lini dies. Barak Sope, leader of Melanesian Progressive Party, elected PM.

2002 Sope convicted of forgery.

2003 Sope pardoned.

2004 President Alfred Maseng steps down when criminal record revealed, replaced by K Mataskelekele. Serge Vohor elected PM, replaced by Ham Lini after no-confidence vote.

2008 Coalition governs under PM Edward Natapei.

2009 Natapei survives no confidence motion.

Father Walter Lini