Repairing “an invisible coat of shame”

Human rights advocate Erin Gough on prying questions, shame, and finding herself worthy.

“So, what’s wrong with you then?”

The tone is as casual as the rest of our conversation about the dreary winter weather.

“… Nothing?” I say, pretending not to know what he is asking.

“I mean…” he replies, gesticulating at my wheelchair.

“I was born.” I state bluntly, trying to make the point that it’s not the tragic accident he likely thinks it is. Here we go again, I think to myself.

He raises his eyebrows expectantly.

Don’t crack, I tell myself. You don’t owe him any information. You would be justified in asking why he thinks a question like that is okay.

But the awkward silence is too much. “…. Too early.” I blurt, “Brain damage. Affects my muscles.”

My answer opens a whole Question Time’s worth of supplementary questions. About how my body does or doesn’t work. And though I want to raise a Point of Order about how it’s really none of his bloody business, I’m not confident enough.

They’re all pretty innocuous in the scheme of things. Can I feel my legs? How long have I used a wheelchair? How fast does it go?

At least he didn’t ask if I can have sex this time. That’s always fun. (It’s not. It’s terrible.)

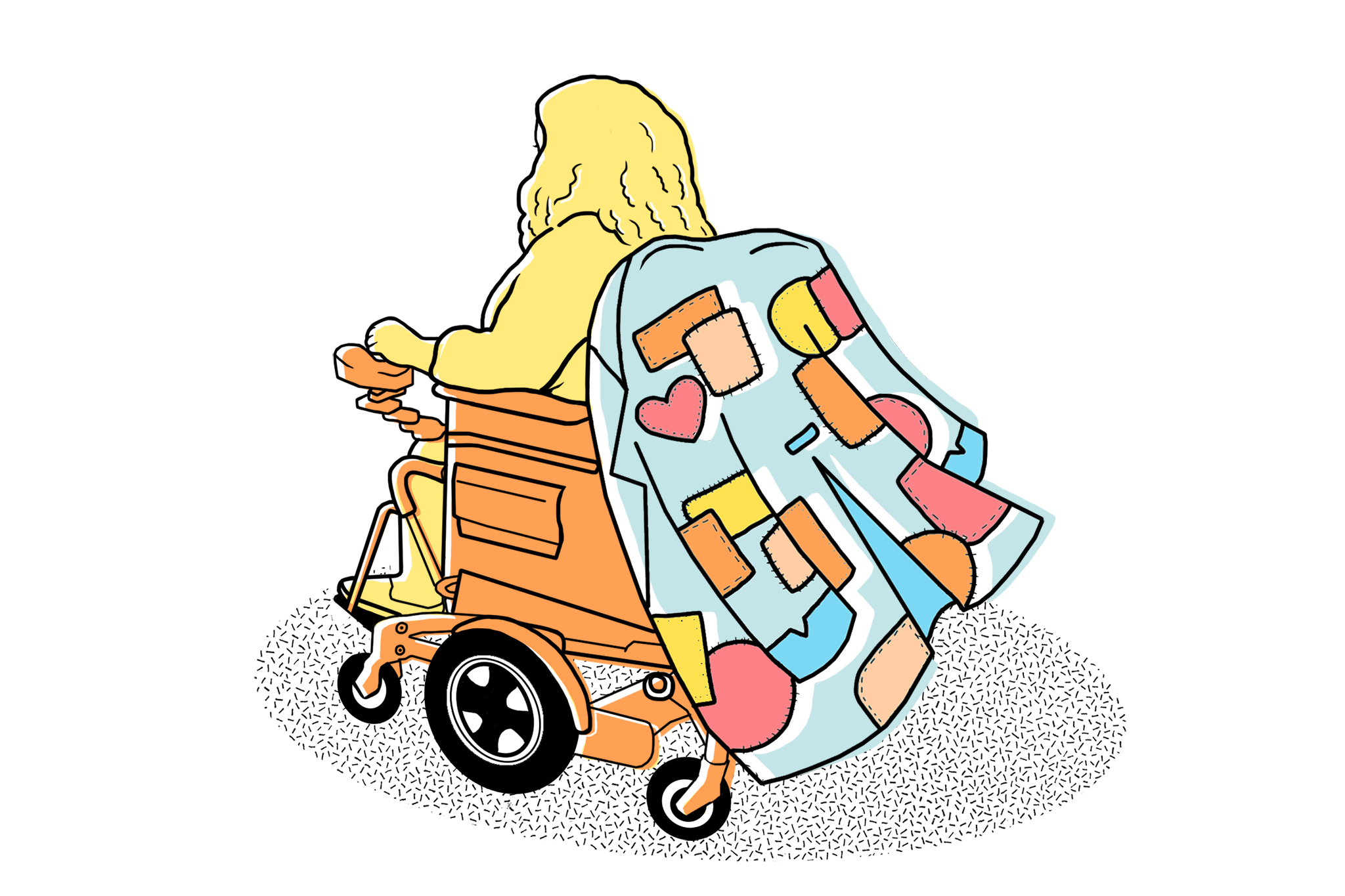

Still, the more he asks, the more I feel exposed, until I’m wearing nothing but an invisible coat of shame.

I’ve worn this coat a lot in my 28 years. It’s heavy, scratchy, uncomfortable. Almost impossible to get out of. And yet, the more I’ve worn it, the better it has fitted.

Unlike other coats I wear, it has no regular pattern or colour scheme. Rather, it’s made up of a mosaic of different sized, coloured and textured pieces of material, woven together with assumptions about the capability, desirability, and worthiness of my body.

the razor sharp, burning red sections are being patched over by a warm, waterproof layer of confidence that comes from knowing it is a blessing in disguise not to be desired by bigots.

There’s the run-of-the-mill beige-coloured “What’s wrong with you?” bits. The taxi encounter darns another one into the sleeve.

The awkwardly placed, oddly-shaped “unsolicited advice about how to ‘fix’ my body bits: yoga, this-medication-a-stranger’s-cousin-with-a-completely-different-condition-takes, prayer.

And the razor sharp, burning red patches. “I like you but I can’t handle dating someone in a wheelchair”, “I’d kill myself if I was disabled”, “I aborted a disabled foetus once.” Those ones hurt the most, no matter how many times I try to blunt them.

Some bits of material are decades old now. Worn, faded, hidden under layers of others. Sewn on when I was just a kid.

Some are more recent. The should(er) pads of being in my twenties. Should have a partner. Should start thinking about having children. Padded with societal expectations.

And some bits intersect with other features of my body. Pockets of fat jokes with ableist and anti-fat linings, double-layered with two kinds of shame material.

I wish I could say I’ve outgrown this coat of shame, but I haven’t. Not yet. But I have been working hard to replace it with better material.

Material made from radical self-love instead of shame, using books like Happy Fat and The Body is Not an Apology as my how-to-guides supplemented by body-positive Instagram accounts showcasing beautiful disabled, fat, queer people of all shades, sizes and body types.

It’s not easy. There’s a heap of material to replace, a lot of stitching to unpick, and, to be honest, I’m just not all that good at sewing. But I’m getting there with practice.

The beige-coloured “things wrong with me” bits are slowly being replaced with brightly coloured “How my visible differences are beautiful” parts.

The awkwardly placed “parts of my body I need to fix” bits are being overtaken by soft, velvety “parts of my body I like” patches.

And the razor sharp, burning red sections are being patched over by a warm, waterproof layer of confidence that comes from knowing it is a blessing in disguise not to be desired by bigots.

And while, despite my best sewing efforts, little bits of shame still peek through sometimes, I can comfortably say that that’s not my, or other disabled people’s shame to carry.

There is nothing wrong with having a body that looks or works differently.

Our bodies are beautiful, just as they are.

We are worthy of love, just as we are.

About the author

Lawyer by training, activist by living, writer by accident, Erin lives in Wellington with two friends and their ginger cat, Wilson.