We need to transcend us vs them struggles, writes Philip McKibbin.

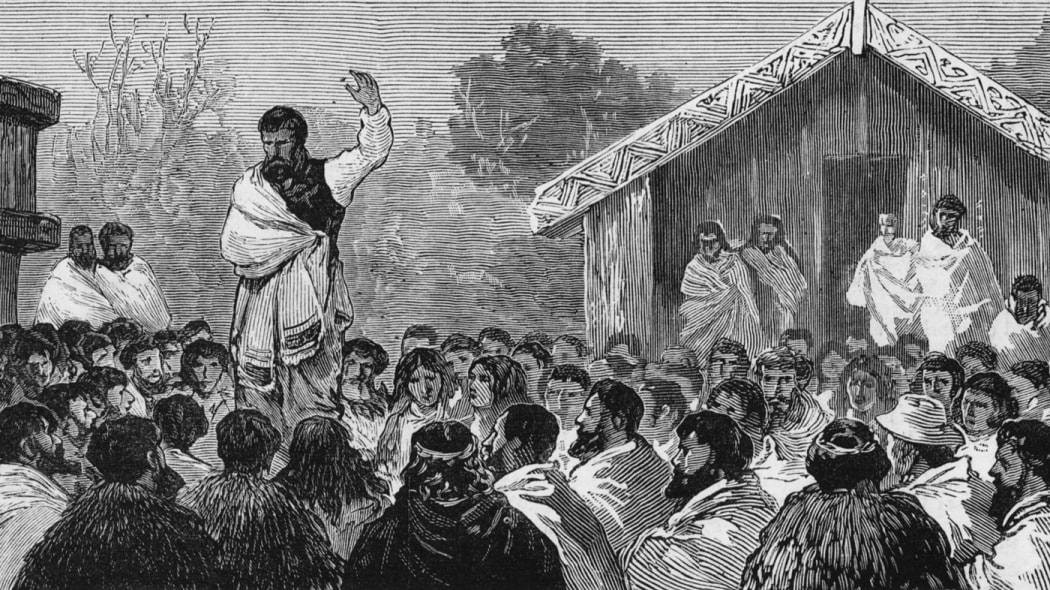

The Prophet Te Whiti Addressing a Meeting of Natives from The Graphic (1881) Photo: do not use - not in public domain

In 1881, the peaceful village of Parihaka was invaded. Fifteen-hundred men, led by the Pākehā Native Minister, assaulted the Māori settlement. Its leaders were arrested, women were raped, buildings pulled down, and crops destroyed.

Two years earlier, Te Whiti o Rongomai had instructed the people to plough land that had been taken from them – an act of passive resistance against its unjust confiscation. The prophet’s instructions were clear: "Go, put your hands to the plough. Look not back. If any come with guns and swords, be not afraid. If they smite you, smite not in return. If they rend you, be not discouraged. Another will take up the good work".

Te Whiti gave us – both Māori and tauiwi – an example of loving politics that continues to inspire us today.

And when the soldiers arrived in 1881, Te Whiti reiterated his call for peace. As he and his whanaunga Tohu Kākahi were being led away, he spoke again to the people, telling them to be "steadfast in all that is peaceful".

In urging the people of Parihaka to resist injustice but insisting that they do so peacefully, Te Whiti demonstrated the basis upon which our peoples might live together in peace. Te Whiti gave us – both Māori and tauiwi – an example of loving politics that continues to inspire us today.

Max Harris and I first sketched the Politics of Love in 2015. It is a values-based politics, which affirms the importance of people and extends beyond us to non-human animals and the environment. The Politics of Love encourages us to imagine our entire politics in loving terms.

As our next general election draws closer, we are faced with another chance to make politics more loving. We’re ready for love. As a nation, we need love more than ever; and we have a history of progressive policy in women’s suffrage, indigenous rights, and homosexual law reform. I believe that the two biggest issues we must now address are inequality and animal agriculture. The Politics of Love insists that we engage with these issues, and suggests how we can approach them.

Inequality has become entrenched in Aotearoa New Zealand. The richest 10 percent of us own more than half our nation’s wealth. This is unacceptable, especially when we consider that between a quarter and a third of our children live below the poverty line, and that homelessness is at an all-time high. The suffering among our people is appalling – as is the cynicism that views it as inevitable. The Politics of Love challenges this attitude, and asks us to look for solutions. Love does not ignore suffering, and it does not resign itself to it: it insists on helping those who are in need.

When I think about inequality, I think of Michael Joseph Savage and the Social Security Act, which was adopted by parliament in 1938. Savage was a politician who, like Te Whiti o Rongomai, suffered with his people. He put his country before himself, sacrificing his health to see the successful implementation of a piece of legislation aimed at assisting the most vulnerable people in our society. His legacy – despite all the attempts at dismantling it – still stands as a bastion of hope, a symbol of what we might accomplish if we make decisions that will benefit all of us.

I am reminded, too, of David Lange and our country’s anti-nuclear stance. Lange, who grew up on the same road that I did, spoke of love in his maiden speech to Parliament, saying, "I believe that our challenge is to create a society where people feel committed to each other, where they have an interdependence which no adversity can force apart, where they realise they have a duty to their brothers, and where the fruits of such a society are seen in the love, the charity and the compassion of the people."

Lange’s own love for people of all backgrounds is legendary in Ōtāhuhu, where he lived and served. In leading our nation’s anti-nuclear policy, he taught us that we can take a moral stand, even when doing so is difficult, and even where it could affect our interests. He showed us, yet again, that Aotearoa New Zealand can set an example for the rest of the world.

If we are to transition to a more sustainable economic structure, we will need to transcend "us" and "them" politics and the "urban/rural" divide.

As we work to address animal agriculture, we might remember our anti-nuclear stance, as well as Lange’s care and concern for people. Animal agriculture causes harm to animals, and it damages the natural environment – and our economy is complicit in this. As well as insisting that we treat animals with respect, the Politics of Love recognises that animal agriculture is one of the largest contributors to climate change, and that, ultimately, this will cause us to suffer.

If we are to transition to a more sustainable economic structure, we will need to transcend "us" and "them" politics and the "urban/rural" divide. As well as speaking for the voiceless, we must ensure that farmers’ voices are listened to, so that we can properly support each other through this challenging transition, and, together, overcome the structural barriers to change.

Although we bear many scars, our nation has a history of loving politics. If we choose to follow the example of those who cared for our people, those who encouraged us to do the right thing because it was the right thing, we will reclaim that history and turn it into tradition.

Over the next month-and-a-half, a lot of attention will be given to voting. We should remember that politics is not just about voting – it can also involve persuasion, voluntary work, formal employment, campaigning, public service, and many other forms of action.

But what about voting? What does the Politics of Love mean for this decision?

When people ask me what guidance the Politics of Love offers, I explain that the first thing it asks of us is that we care: about each other, and about politics. When it comes to the election, we need to take our choice seriously, and involve ourselves in the debates – then, we need to vote.

I will be among the first to say that just because a politician mentions love does not mean that their politics is loving: during his campaign for president, Donald Trump repeatedly referred to love – as when he declared his love for Mexico – while pushing a politics of fear.

The Politics of Love asks us to look beyond words, and vote on values. Loving values, such as compassion, responsibility, and trust are central to this politics. We can judge a party’s values by its policy proposals, its past policies, and their outcomes, as well as by its politicians’ words and actions. The Politics of Love urges us to judge these lovingly, and vote accordingly.

The Politics of Love is within our reach. We are ready for loving politics, and the history of our nation gives us inspiring examples to follow. It is up to us, now, to realise it.

Philip McKibbin is an independent writer from Aotearoa New Zealand. He holds a Master of Arts in Philosophy from the University of Auckland.