Sixty years ago, US President Dwight Eisenhower gave currency to the expression the military industrial complex - the relationship between a country's military and the defense industry that supplies it.

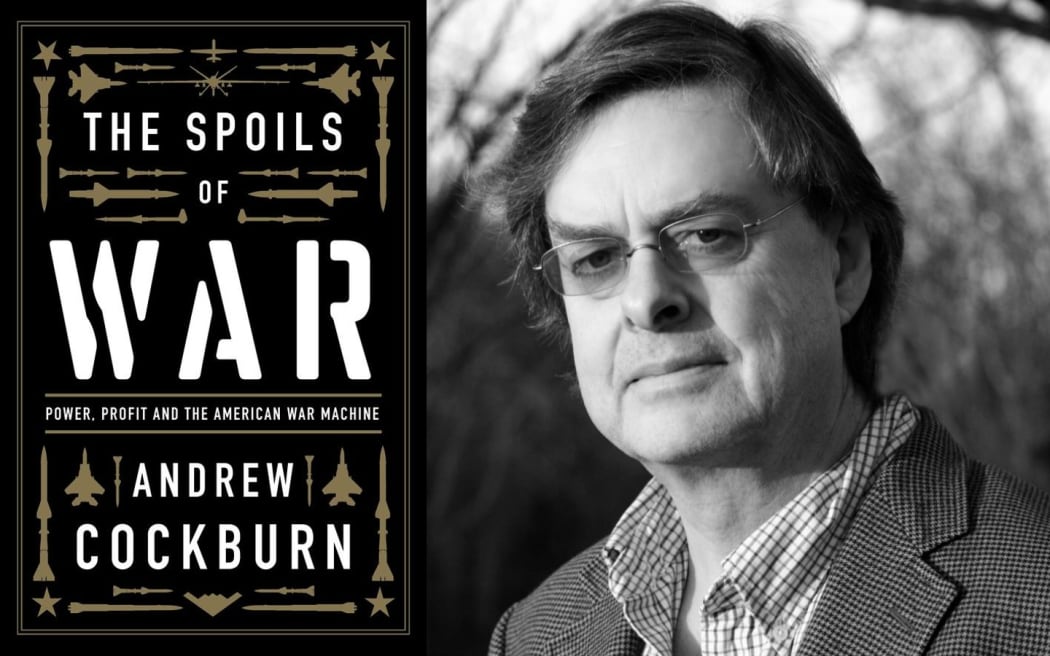

And that complex remains as strong as it ever was according to investigative reporter and Washington editor of Harper's Magazine, Andrew Cockburn.

Photo: AFP / FILE

Cockburn has devoted a large part of his career examining the military industrial complex. And his latest book is a collection of his articles on the subject - The Spoils of War: Power, Profit and the American War Machine.

In it, Cockburn expands on his theme that the United States' appetite for war is driven by the military's eagerness for evermore money shared with the corporations that feed off it, as well as the officers who will cash in with high paid employment with those same corporations once they retire.

In his book, he gives examples of enormously expensive military hardware being deployed for jobs for which it is entirely unsuited.

The B1 bomber at a price of $US300 million, is a case in point, he says.

"It's very stupid to be using a $300 million bomber, which was originally developed and designed to go to Moscow at supersonic speeds and drop nuclear weapons …. to protect small units of American soldiers on a mountain somewhere in Afghanistan."

But if you follow the money the picture is different, he says.

"But if you think, hey $300 million to important corporations across America, and part of that will come back in the form of, not just votes from workers, but campaign contributions, jobs for generals when they retire, profits all round, then it's a very sensible way to proceed, you just have to think about what is really at stake."

On this basis, Afghanistan was an enormous success for the US military, he says. As trillions of dollars flowed into the military industrial complex.

It is institutionalised corruption, he says.

"It is corrupt to pursue a war if the object is to make money, or to get money if your institution."

A contact he has used as background for stories gave him an anecdote to support the idea that money drives war.

"A military officer, a friend and contact of mine, who was a staffer at that point, on the headquarters staff.

"And Donald Trump has just announced a little mini surge in Afghanistan, he'd been persuaded to send more troops temporarily.

"And the generals, these were all four-star generals discussing this and saying, well, it won't make any difference in the war. But it'll do us good at budget time. It'll be more money for our service."

John Sopko, the Special Inspector General for Afghan reconstruction, told Coburn that the entire system in Afghanistan was geared towards waste.

"The incentive is you get judged on how much money you spend, you're given $100 million, your budget is $100 million, and you're judged, successful or otherwise, depending on whether you spend that money.

Photo: Supplied

"And if that money is misspent or is wasted on things don't doesn't work, there's no sanction, there's no accountability.

"If there's no disincentive to make sure the thing you're spending money on works, or is effective, then it's going to fail, obviously."

Not one senior military official or bureaucrat was ever sanctioned for the eyewatering waste that went on over 20 years in Afghanistan, he says.

"They were all rewarded for doing what the system said they should do, which was to spend money."

No matter who is in government, the military industrial complex prevails, Cockburn says.

"It doesn't really matter who's in power, the budget overall has increased at a steady rate since 1954, for military spending it has been 5 percent a year.

"Whenever it dips below, it doesn't matter who's in power, whenever it seems to be dipping below that trend, someone discovers a huge new threat, a missile gap or budget spending gap or a missile defense gap, it doesn't matter. Something comes along to protect it."

There have been precious few peace dividends, he says. Spending after the Vietnam war and Cold War ended soon resumed at previous levels.

"You'd think there'd be a big cut in defense spending? Not so, it dipped a little bit in both cases, but for not very long and soon it was up beyond to its former levels."

The war in Afghanistan effectively fed the military beast, he says. It had little strategic point.

"I'm not speaking up for the Taliban in any way, a very noxious bunch, clearly.

"But on September 11, 2001, the US was attacked by a bunch of Saudis."

Saudi Arabia however was too important an ally to take revenge upon, he says,

"We knew by September 12, 2001 that the 15 of the 19 hijackers were Saudis.

"And the next thing we saw was a picture of the Saudi ambassador, on the balcony of the White House smoking cigars with President Bush.

"The problem is that Saudi Arabia is too important, bringing us back to our main topic, to the military industrial complex as a huge outlet for US arms sales."

And yet the war in Afghanistan rolled on for two decades.

"Even though al Qaeda had gone from Afghanistan in a matter of weeks, we stayed on for 20 years, bombing and killing there.

"So, it was definitely a war of choice, very much dictated by the need to feed the beast."