“We knew Raoul Island was a humpback whale meeting place, but I didn’t appreciate how many different places they would be coming from.”

Rochelle Constantine, University of Auckland

A young humpback whale leaps out of the water near Raoul Island in the Kermadecs Photo: Becky Lindsay / University of Auckland

A humpback whale dives next to a small inflatable boat and a team of scientists attaching satellite tags to whales. Photo: Olive Andrews / University of Auckland

Rochelle Constantine, from the University of Auckland, and her colleagues have been on the tail of Oceania’s threatened humpback whales for many years.

They have wondered why their numbers are growing so slowly compared to the humpbacks of east Australia, and whether it was to do with their undiscovered Antarctic feeding grounds.

Rochelle has heard reports of humpback whales visiting Raoul Island, in the Kermadecs, in spring. They were heading south from their tropical breeding grounds, to their summer feeding grounds, and they were there in numbers - Department of Conservation workers on the island counted more than 150 whales in a single 4-hour period.

She also wondered if they were travelling from the Oceania breeding grounds around New Caledonia, Niue, Tonga and the Cook Islands.

In 2010, Rochelle was part of an expedition to the Ross Sea area of Antarctica, where she hoped to find the Oceania whales. But electronic tagging, photo-identification and genetic matching of humpbacks from the Ross Sea and the Balleny Islands showed that these were east Australian whales.

Since whaling finished the humpback whales of eastern Australia have bounced back strongly, and now number more than 25,000.

Twenty four whales were tagged with satellite tags at Raoul Island in October 2015. The silver dot on the whale is the tag. The red & silver object is the ‘rocket’ that the tag sits in when fired from the tagging gun; when the tag hits the whale the rocket detaches. The yellow- and red-ended object is the biopsy dart – it has a small stainless steel cutting tip sticking out of the yellow end to take a small tissue sample. It then falls into the water and can be retrieved by the tagging team. Photo: University of Auckland

In October 2015, the Great Humpback Whale Expedition headed to Raoul Island to tag and survey the humpback whales, and the team of seven researchers successfully tagged 24 of them with tiny satellite tags.

They also took photos of the underside of the whale’s tails, which allow them to be individually identified, and the Raoul Island humpback whale catalogue now includes 133 whales.

While they were at Raoul Island they recognised one whale from Niue, and that one of them was first seen at New Caledonia in 1999 as a calf. Now an adult, the whale was being accompanied by her own newborn calf.

The team also collected 78 tissue biopsies from the tagged whales that allowed them to genetically match four of the Raoul Island whales to the Oceania humpback whale population. The tissue can also be used in stable isotope analysis to identify what the whales are eating.

Rochelle says that they started using a new technique called isoscale analysis, which allows them to identify which area of the ocean a whale is feeding in.

“When a whale eats an animal like krill, the chemistry of the ocean that’s in the krill is now in the whale, and we’re able to assign where that whale is feeding, using the ocean chemistry.”

There are 133 individual whales in the Raoul Island humpback whale catalogue. They are identified from the unique patterns on their tail flukes. Photo: University of Auckland

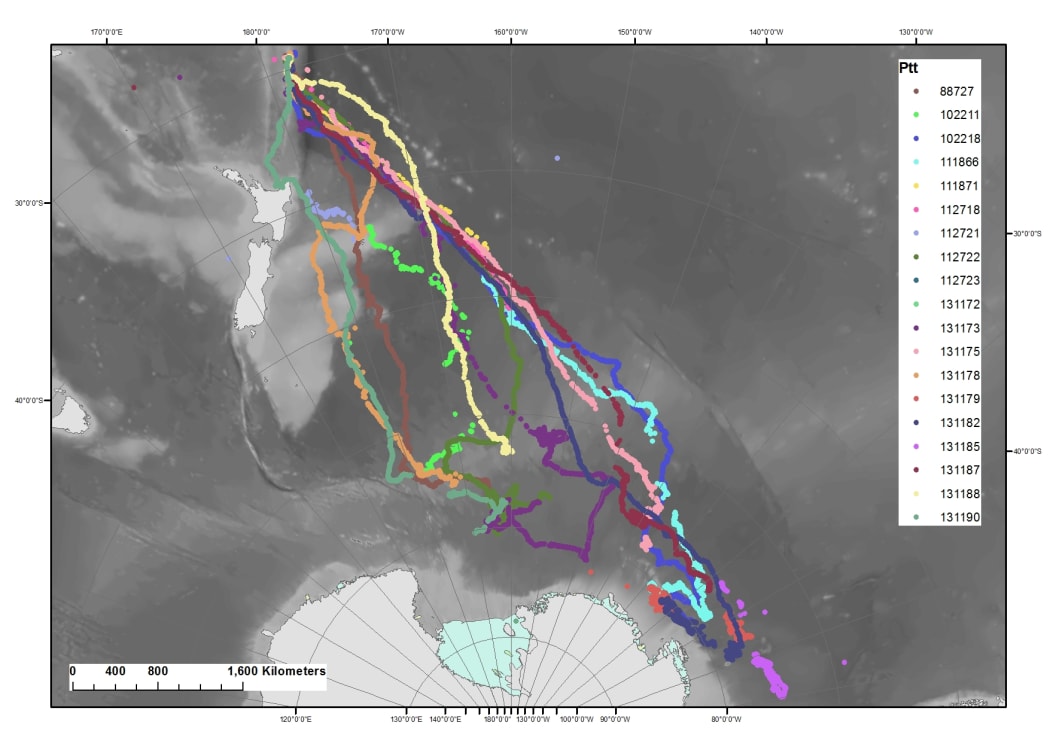

The satellite tags showed that the humpback whales from Raoul Island moved in a south-east direction towards Antarctica. They spread out across a 3000km area of Antarctica, from the Ross Sea, Amundsen Sea and Bellinghausen Sea, almost as far west as the Antarctic Peninsula.

“From Oceania to Raoul Island is about 1600 kilometres,” says Rochelle. “Our longest whale journey from Raoul Island to Antarctica was 7000 kilometres, and it took [the whale] nine weeks to swim that far. So it’s about 8500 kilometres one-way.”

The great humpback whale trail: this map (dated 4 April 2016) shows the routes taken by 24 whales tagged with satellite tags at Raoul Island, as they travelled to a range of places in Antarctica, from the Ross Sea to nearly the Antarctic Peninsula. Photo: University of Auckland

Rochelle thinks that the long journey undertaken by the Oceania whales may be part of the reason that the population is recovering slowly.

The research also confirmed that Raoul Island is an important meeting and socialising place for whales, and one of the striking observations was that there was a wide range of whale songs being sung.

Whale songs are culturally transmitted, and the songs move across the Pacific from west to east over several years. Rochelle and the team wonder if Raoul Island plays a special role in the transmission of songs.

“Maybe Raoul Island is one of those places where this cultural handover of song information takes place.”

In October 2015, the New Zealand Government announced it would create a 620,000 hectare ocean sanctuary at the Kermadecs. The Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary Bill is currently before Parliament.