This picture shows white gaseous clouds rising from the Hunga Ha'apai eruption. Photo: Mary Lyn Fonua

A new report has revealed Tonga's underwater volcano disaster triggered waves up to 90 metres high.

The University of Miami and the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation report states the eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano last year was more powerful than the largest US nuclear test.

The study involved the collaboration of scientists from numerous agencies including NASA, NIWA, and the Tonga Geological Service.

The report's authors said their simulated peak height of the largest blast, number five in the sequence, was 85 metres.

"Immediately after the explosion, the transient blast cavity that becomes the tsunami is 6km across, forming a wave 85m high on the north side of HTHH and 65m high to the south.

"The wave runups from the 2022 HTHH explosive event comfortably meet the criteria for a megatsunami and contend for the largest event anywhere in the past 100 years."

Watch a simulation of the eruption.

One of the co-authors, Auckland University professor Shane Cronin, said the findings increasingly showed what a monumental event the eruption was.

"Everything we knew about the explosive power of submarine volcanoes has been completely thrown out the window," he said.

Cronin was one of the first academics to visit the post-eruption site of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano.

"We realise from this eruption that there's a whole type of volcanic activity of submarine volcanoes that we never imagined could happen," he said.

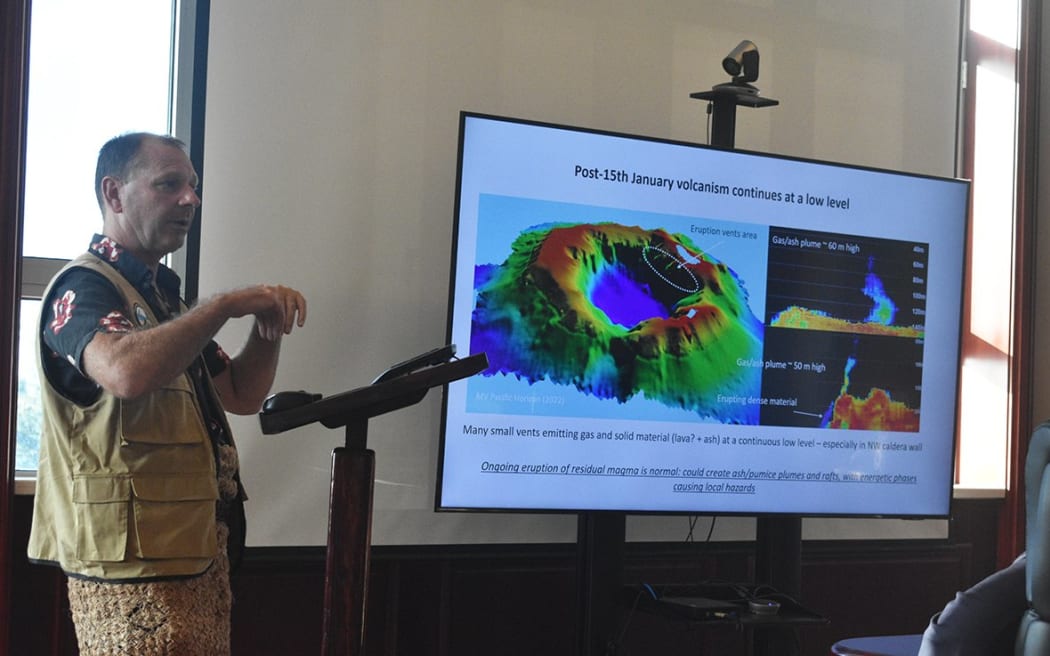

Professor Shane Cronin Photo: Tonga Geological Services

"It's really opened up our eyes to another type of volcano and now that we've seen this example we can now start to better understand other submarine volcanoes."

The record-breaking volcano was 500 times more powerful than the bomb that hit Hiroshima, generating a mushroom cloud which penetrated the atmosphere and was visible from space.

It was the largest eruption since the Krakatoa eruption in Indonesia a century ago, generating one of the largest sonic booms ever recorded.

"We went around measuring all the places where the tsunami waves ran up using drones and survey equipment," Cronin said.

"The waves went right up and above two islands near the caldera, so the waves must have been at least 85 to 90 metres to have gone above those islands.

"The wave rises up but it always loses a lot of energy and it hit a very extensive area of reef and shallow water, so by the time it reached Nuku'alofa, the wave had dissipated.

"It's a blessing for our knowledge."

'Blessing in disguise'

Tonga Geological Service head Taaniela Kula was present during the devastating eruption on 15 January, 2022.

From a scientific point of view, he described the eruption as a blessing in disguise.

"The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai eruption was one of a kind," Kula said.

"Before January 15th, we'd never heard of an undersea eruption that's reached beyond the atmosphere.

"There's now a lot of interest from overseas volcanologists … and it's a good opportunity to better understand volcanoes in Tonga.

"We have more than 50 submarine volcanoes that we need to map out and better understand … studies will be ongoing and long term."

Taaniela Kula and Professor Shane Cronin, Tonga Geological Services Photo: Tonga Geological Services

Undersea volcano eruptions were a common phenomenon in Tonga, and they explained many of the geological characteristics of country, Kula said.

Tonga's main island of Tongatapu is known for having very fertile soils, the reason for which had been a puzzle for scientists until the eruption.

"We've always known that the content of our soil in Tongatapu and 'Eua is fertile because of volcanology, but we couldn't explain how these fertile soils were deposited, because the nearest volcanos are 70km away and we assumed volcanic ash from submarine volcanic eruptions couldn't fall more than 20km from the source," Kul said.

"That changed on January 15th, because we realise now that submarine volcanoes can submerge from the seafloor and spit out tonnes of cubic materials far out onto islands and make them fertile.

"We're bearing fruit four times a season now because of the fertility of the soil, because of the mineral rich ashfall from the eruption."

year since the eruption, watermelon production has skyrocketed thanks to mineral rich ashfall. Photo: Finau Fonua

Another geological characteristic explained by the eruption was the presence of massive boulders on Tongatapu including a 1600-tonne rock located near a beach in Tongatapu - known as Maka Tolo 'a Mau. According to Tongan mythology, the boulder had been thrown by Maui at a rooster that was annoying him.

"Nobody could imagine how a three-storey boulder ended up here," Kula said.

"Now we know it was from the waves caused by a submarine eruption."

Kula said the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai eruption also revealed large tsunami could be generated by undersea eruptions.

"We had always visualised tsunami generated by volcanic eruptions as being formed by the collapse of the walls of volcano into the ocean.

"It was only when this event occurred that we realised there's another way a tsunami caused by an eruption can be formed."

Public awareness and geographical quirks saved lives

Perhaps the most astonishing phenomenon of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano was not the nature of eruption, but the remarkably low casualty rate of the disaster.

Only three people died, all from the tsunami waves generated by the eruption. It is a remarkably low casualty thanks to the quick self-evacuation of the Tongan public to higher ground.

"At the beginning, we were astonished that the casualty rate was so low," Cronin said.

"When I spent four months to do follow surveys, I realised why it was so low, because the public education about the dangers of tsunami was really good and had been going on for many years," he said.

"It all took place on a Saturday afternoon, so it was easily visible and when people heard the eruption, they immediately did the right thing and moved inland."

A tsunami drill at a school in Tonga Photo: Tonga National Emergency Management Office